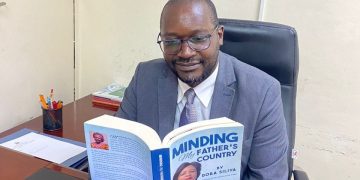

Kampamba Shula[1]

Abstract:

This article discusses the critical issue of public debt reform in Zambia, which has a long history of borrowing to finance infrastructure development and economic growth. The country has been grappling with a high level of debt for years, with recent challenges related to debt sustainability and default, worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic. One of the recent developments in Zambia’s debt reform efforts has been the Dipak Patel vs. Attorney General Case, which was heard by the Constitutional Court in 2020. The case had significant implications for the country’s debt management practices, as it questioned whether the Zambian government needed parliamentary approval for external borrowing. Despite clear provisions in the Constitution that require such approval, the Constitutional Court dismissed the petition, potentially undermining transparency and accountability in debt management practices. The article concludes by emphasizing the urgent need for public debt reform in Zambia, and the hope that legislative proposals will be tabled that will give genuine effect to the oversight functions of the National Assembly. The article recommends that parliamentary oversight of debt management practices in Zambia be strengthened through the National Assembly’s expanded Budget Committee to be responsible for examining public debt before it is contracted, in line with the appropriate National Assembly Standing Orders.

Keywords: Zambia, Public Debt Reform

Citation:

Shula, K. (2023). Zambia’s Public Debt Reform. Working Papers, Volume 2023, April. Lusaka

URL:

https://kampambashula.academia.edu/

Introduction

Public debt reform has been a critical issue in Zambia, with the country grappling with a history of high levels of debt and recent challenges related to debt sustainability and default. Zambia has a long history of borrowing to finance infrastructure development and economic growth, but this has come at a significant cost, with debt levels rising steadily over the years.

Zambia has been grappling with a crippling debt burden for several years. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated its economic challenges, leading the country to default on its debt repayments in November 2020. The government subsequently entered into negotiations with its creditors to restructure its debt and stabilize its finances. In 2020, Zambia became the first African country to default on its debt during the COVID-19 pandemic, after failing to make a $42.5 million interest payment on its Eurobond. This default highlighted the challenges facing Zambia’s debt sustainability, including high levels of debt servicing costs, low foreign exchange reserves, and limited fiscal space.

One of the recent developments in Zambia’s debt reform efforts has been the Dipak Patel vs Attorney General case, which was heard by the Constitutional Court in 2020. The case centered on whether the Zambian government needed parliamentary approval for external borrowing, and it had significant implications for the country’s debt management practices.

The petitioners argued that the government had violated the Constitution by borrowing without the approval of the National Assembly. They contended that the Constitution required such approval, and that the government’s failure to seek it was a breach of the law. However, the Constitutional Court, by a majority decision, dismissed the petition, finding that the requirement for National Assembly approval was not mandatory.

This ruling has significant implications for debt management practices in Zambia, as it potentially undermines the role of the National Assembly in approving external borrowing. It suggests that the government can borrow without parliamentary approval, which could make it more challenging to ensure that debt management practices are transparent and accountable.

Furthermore, the Constitutional Court erred by ruling that parliamentary approval was not mandatory, as other articles in the Constitution of Zambia clearly stipulate that parliamentary approval is required for external borrowing. For instance, Article 63(2) of the Constitution provides that “the National Assembly shall have power to authorize by resolution, the raising of loans.” Therefore, the court’s decision goes against the spirit of the Constitution and could set a dangerous precedent for future debt management practices in Zambia.

In conclusion, public debt reform is a critical issue in Zambia, and the recent increase in debt levels, debt default, and legal challenges related to debt management practices underscore the urgent need for reform. The Dipak Patel vs Attorney General case has highlighted some of the challenges facing debt management practices in Zambia, and the court’s decision could potentially undermine efforts to ensure transparency and accountability in debt management practices. Without prejudice to the above, as Zambia comes to terms with the years of unencumbered public borrowing, there is a need for introspection by the new administration in how it tackles borrowing in the future. There is hope that legislative proposals will be tabled that will give genuine effect to oversight functions of the National Assembly.

Background

Early 2000s – Movement for Multiparty Democracy Administration

It is tempting to presume that Zambia’s problems of ineffective public debt management reforms began during the last ten years. However this is not quite accurate as this problem was prevalent even 20 to 30 years ago. Zambia qualified for HIPC debt relief assistance at decision point in December 2000[2][i]. As far back as 2004, these debt reform problems were masked over by Zambia reaching the HIPC completion point. On April 8, 2005 Zambia became the 13th regional member country to reach the completion point under the enhanced HIPC Initiative. As a result, the Boards of Directors of the IMF and the World Bank approved a total irrevocable debt relief from multilateral and bilateral creditors amounting to US$ 2.5 billion in end-1999 NPV terms (US$ 3.9 billion in nominal terms).

With technical assistance from IDA and other cooperating partners. Government had prepared a public debt management reform program, which was to be implemented over the next few years to remedy this situation. The situation, as time would show us, gradually and somewhat exponentially became worse.

After 2011 – Patriotic Front Administration

Fiscal prudence stems from the economic philosophy of the political administration in Government. By 2011, there was fragility in both public finance and public debt management reforms. The legislative framework for both public debt and public finance management had not been updated, precipitating in events that transpired with the oncoming of the Patriotic Front administration in 2011.

Zambia took on a highly expansionary fiscal path in 2012 when the Patriotic Front (PF) political party assumed office of the Government (Shula, 2020). The PF Manifesto 2011-2016 asserts that: “Under the MMD government, investment in infrastructure development has been limited and the pace of development slow. Part of this is due to an obsession with maintaining ‘tight money’ through fiscal and monetary policies. This has resulted in many parts of Zambia resembling ghost towns despite more than five years of record mineral prices and a production boom”.

The PF Manifesto thus inevitably locked the then new Government into a very ambitious infrastructure development programme, thus ushering in fiscal expansion. The real growth rate of the national budget rose from 2.1% per annum during 2002-2011 to 10.2% per year during 2012- 2018 despite the severe hikes in inflation in 2015 and 2016.

In 2013, a statutory instrument No 116 of 2013[3][ii] was introduced. In an appearance before the committee on delegated legislation for the third session of the eleventh national assembly, Permanent Secretary (Budget and Economic Affairs) submitted that the Loans and Guarantees (Maximum Amounts) (Amendment) Order, 1998 prescribed ZMW20 Billion as the maximum amount of loans with maturity of more than one year that the Minister of Finance could raise outside the country. The maximum amount provided under the Order had to be increased further if the Minister of Finance had to raise loans under the Act and be able to finance the budget in 2014 and the 2014-2016 Medium Term Expenditure Framework.

The National Assembly, by resolution, authorised the Minister to increase the maximum amount of loans that could be raised from outside the country under the Act to ZMW35 billion in line with the provisions of the Loans and Guarantees (Authorisation) Act of the Laws of Zambia. This Statutory Instrument was issued and published on 29th November, 2013 to effect the resolution of the National Assembly to increase the maximum amount to ZMW35 billion to enable the Government to raise external loans to finance the budget.

In March, 2014, the Minister of Finance moved a motion in Parliament to amend the Loans and Guarantees (Maximum Amounts) Order, Statutory Instrument No. 116 of 2013 to adjust the maximum amounts of outstanding domestic loans and total amounts of internal and external guarantees that the Government may issue.

The Minister proposed an increase in the maximum amount of loans outstanding at any one time raised within the Republic and payable over a period of not more than one year from K200 million to K13 billion and from K10 million to K20 million for loans outstanding at any one time raised within the Republic and payable over a period of more than one year.

It was realized that these thresholds had been exceeded and required adjustments to comply with the provisions of the law. Instead of plans to lower the amount of loans held, the prevailing view was to adjust the thresholds upwards instead. This proved to be the beginning of a sequence of events that would have consequences later. The Loans and Guarantees (Authorisation) (Maximum Amounts) Order, No. 116 of 2013 was, therefore, amended on 21st March, 2014[4][iii]. The amendment brought the total outstanding domestic loans and total outstanding external guarantees within the confines of the law.

Figure 1 Fiscal Deficit

Source: Ministry of Finance

By 2015, Zambia’s fiscal deficit had increased from 2.2 per cent of GDP in 2012 to 4.5 per cent of GDP in 2014. The deficit increased to 5.7 per cent of GDP in 2013 compared to the 2014 out-turn of 4.5 per cent. The key drivers of this deficit were less than projected revenues and the budget overrun. Domestic revenue averaged 18 percent of GDP from 2012 to 2014, during that period expenditure in absolute terms averaged 21.7% over the period 2011 to 2014. Zambia was not earning enough to meet its expenditures.

At the time, admittedly, the projected fiscal deficit was still within sustainable levels. However, there were concerns from various stakeholders about the seemingly high rate at which the deficit was increasing. There were fears that if left unchecked, the economy might fall into a debt trap as experienced during the pre-HIPC completion point of 2005.

On 1st April 2016, Minister of Finance Alexander Chikwanda[5][iv] created a statutory instrument to amend the maximum amounts of loans raised within and outside the republic. This included loans payable within the Republic over a period not more than one year and more than one year to ZMW30 Billion and ZMW40 Billion respectively. The amount outstanding at any given time on loans raised outside the Republic with maturity of more than one year was capped at ZMW160 billion.

On 9th April, 2018 the long awaited Public Finance act[6][v] was assented to provide for an institutional and regulatory framework for management of public funds, the strengthening of accountability, oversight, management and control of public funds in the public financial management framework.

Case Review – Dipak Patel vs. Attorney general

In 2016, the Constitution of Zambia was amended, introducing a provision that required the National Assembly to approve all debt before it was contracted. The Constitutional amendment also introduced a requirement that legislation relating to the contraction and guaranteeing of debt should provide the category, nature and other terms and conditions of a loan, grant or guarantee that will require approval by the National Assembly before the loan, grant or guarantee is executed. Unfortunately, since the constitutional amendment in 2016, the government of Zambia acquired numerous loans without the approval of the National Assembly of Zambia. The Petitioner, a former Minister[7][vi], petitioned the Constitutional Court alleging that the Minister of Finance and the Government had violated the Constitution by acquiring debt without the prior approval of the National Assembly of Zambia. The Petitioner also alleged that the Loans and Guarantees (Authorisation) Act was unconstitutional as it failed to mandate the Executive to seek approval for debt before it was contracted.

Lady Justice Munalula[8][vii], in her dissenting opinion, found that the government had breached the law by not presenting debt for approval before it was contracted in the dissenting judgment.

Contrary to the findings in the majority judgment, National Assembly oversight in debt contraction is not only to mitigate high indebtedness. Instead, National Assembly oversight over debt contraction is rooted in the principles of separation of powers and checks and balances. Quite simply, while the Executive is responsible for raising revenues and spending the said revenues, the Constitution does not envisage that this should occur without the National Assembly’s oversight.

As the UPND led administration tackles the debt accrued by the previous administration, it has embarked on a borrowing campaign in much the same way it was before. Perhaps encouraged by the decision of the Constitutional Court, the new administration has announced several public financing agreements, including the announcement of a Staff-Level Agreement with the International Monetary Fund. Particularly alarming is that the direction taken by the new administration is in stark contrast to the pre-election rhetoric issued about debt contraction. The current Minister of Finance made a witness statement in the Dipak Patel Case.

Another significant finding in the majority judgment was that the Constitutional Court[9], despite finding that there was no mandatory requirement for National Assembly to approve debt before it was contracted, the Constitutional Court stated, that the Loans and Guarantees (Authorisation) Act ‘must be amended, repealed or replaced as the case may be. The Constitutional Court has repeatedly stated that no constitutional provision should be read in isolation. In the absence of a law providing the said categories, nature and conditions that require National Assembly approval, the provisions of Article 63 (2) should not be read restrictively.

Several the Constitutional Court judgments, the Court has gone to great lengths to discuss principles of interpretation. Article 267 of the Constitution provides the primary rules for interpreting the constitution. Among the canons for interpretation in the constitution is the requirement that interpretation must promote the Constitution’s purposes, values, and principles and contribute to good governance. The interpretation of the Constitutional provisions, in this case, did not adequately address the purposes, values and principles of the Constitution. In addition, the judgment did not contribute to good governance.

On the contrary, it perpetuates the unlimited Executive trope that undermines good governance. For example, the National Assembly is responsible for appropriating funds for expenditure and ensuring equity in the distribution of national resources; any borrowing the government undertakes falls within the National Assembly oversight functions. That is to say; the National Assembly must ensure that borrowed monies are equitably distributed and appropriated for expenditure in accordance with the law. The judgment in effect creates an exception to this procedure. For instance, the Minister of Finance recently announced a loan from the World Bank to build schools in previously neglected places. This announcement, in effect, is the Executive appropriating funds which is a function of the National Assembly. As the Court has repeatedly stated, Constitutional provisions must not be read in isolation. However, they should not be interpreted in isolation either. The role of the National Assembly in debt contraction is to ensure that constitutional principles such as transparency and accountability are upheld.

This case highlights a flaw in our parliamentary system in that National Assembly has not been proactive in curbing executive excesses.

National Assembly approval of debt occurs in two ways, the first is supposed to be through the National Assembly procedure for approving executive decisions, and the second is through the National Assemblies participation in the passing of legislation. So far, the National Assembly has not been proactive in requiring the executive to provide information of loans it takes out. Further, the National Assembly, as part of the parliamentary business, has been a passive bystander in legislative processes. The Executive often drives the legislative process in Zambia. There is little involvement from a policy perspective from Members of Parliament. This means that legislative proposals presented to the National Assembly usually go through with limited scrutiny in several instances.

How National Assembly approves debt before it is contracted should predominantly be a matter for National Assembly procedure rather than the legislative process[10]. Article 77 (1) provides that the National Assembly shall regulate its procedure and make Standing Orders for the conduct of its business. In this regard, the National Assembly Standing Orders provide that one of the functions of the Budget Committee is to examine public debt before it is contracted.

However, in her opinion, Lady Justice Munalula suggested a ‘suspension of the declaration of unconstitutionality’ as a solution for avoiding the negative impact of such a declaration[11]. This approach implies that the Constitutional Court has the authority to suspend compliance with the constitution temporarily. Constitutional supremacy is a fundamental principle of constitutional democracies like Zambia. The Constitutional Court has reiterated this position repeatedly. Therefore, article 2 (b) of the Constitution provides that every person has a duty to prevent a person from suspending or illegally abrogating the Constitution.

Significance

The Constitutional Court has repeated on several occasions in cases such Steven Katuka and Others[viii][12] v. the Attorney-General and Others and the Public Protector for the Republic of Zambia v. Indeni Petroleum Refinery Company Limited[13][ix] that the primary principle of interpretation is that the meaning of the text should be derived from the plain meaning of the language used.

Specifically, in the Public Protector for the Republic of Zambia case, the court held that:

In other words, where the words of any provision are clear and unambiguous, they must be given their ordinary meaning unless this would lead to absurdity or be in conflict with other provisions of the Constitution.

The holding above makes it clear that when the Constitution is interpreted[14][x], the meaning of each provision should be construed in such a manner that it gives effect to the ordinary meaning of the words – unless it would lead to an absurdity or conflict with other provisions of the Constitution.

According to the court in Martin Musonda[xi], the Constitution should be read so that all matters touching on the matter which is the subject of interpretation are considered. This is important because all interpretation of Constitutional provisions should be guided by the need to give effect to objectives of the Constitution.

In Matilda Mutale v. the Attorney General and Emmanuel Munaile[xii] , the Supreme Court had the occasion to interpret the meaning of “shall” in legislation and held that where the word does not carry any technical meaning to require further elaboration as to the true intention of the legislature, the word “shall” should be

interpreted as being mandatory.

Where a power is assigned to a body or decision-maker in terms of legislation, only that party is permitted to exercise that power. The Supreme Court in Embassy Supermarket v. Union Bank[15][xiii] (in liquidation) was clear that:

Where a statute places duty on an individual or officer no other person shall perform that duty unless it is so provided for under the same law.

Based on the above and a literal reading of Article 63(2) (d) of the Constitution, the power to approve debt vests in National Assembly and there is no proviso or exceptions to this power. Based on the Embassy Supermarket case, the National Assembly is the sole body tasked with approving public debt and thus approval is needed for all public debt, subject to legislation in Article 207(2) (a), contrary to the position taken.

The mere fact that Article 207(2)(a) requires legislation to provide the category, nature and other terms and conditions of public debt that need approval by the National Assembly does not mean that the National Assembly does not have oversight over all public debt.

Nothing in Article 63(2)(d) nor Article 207 suggests that there are exceptions to the need for National Assembly approval and thus the court was wrong in this regard. This is clear from the wording of Article 114 which states that the Executive must recommend loans or guarantees on loans for the approval of the National Assembly. This clearly illustrates that the National Assembly has the mandate to approve all public debt when Articles 63(2) (d) and 114(1)(e) are read together. Had the Constitutional Court taken this approach, a different outcome would have been reached.

The Constitution merely requires legislation to provide specific provision not exceptions to the role of National Assembly[16]. In other words, the requirement that the National Assembly must approve public debt is unqualified and not subject to any proviso and any legislation that would be contrary to this position, as it would be unconstitutional. In this regard based on the Constitution itself, the National Assembly is mandated to approve all public debt, contrary to the position taken by the court.

Crucially Article 63(2) (d) is subject to Article 207(2) (a) of the Constitution which states that:

(2) Legislation enacted under clause (1) shall provide—

(a) For the category, nature and other terms and conditions of a loan, grant or guarantee, that will require the approval by the National Assembly before the loan, grant or guarantee is executed

The above makes it clear that legislation should be enacted to provide for the category, nature and other terms and conditions of a loan, grant or guarantee, which will require the approval by the National Assembly. This is an important provision which illustrates that in addition to the general power given to the National Assembly to approve public debt, legislation needs to be enacted to outline the categories, nature, terms, and conditions of the public debt that will require approval.

Based on their analysis of these provisions, the Constitutional Court concluded that there is no mandatory requirement in Article 63(2)(d) of the Constitution to submit all loans for approval to the National Assembly.

However, the majority decision of the Constitution Court failed to take into consideration Articles 8 (e), 9(1) and 267 (1) of the Constitution which are relevant to the case at hand. Article 8(e) provides Good Governance and Integrityas one of the core national values and principles. Article 9(1) states that:

(1) The national values and principles shall apply to the –

(a) Interpretation of this Constitution;

(b) Enactment and interpretation of the law; and

(c) Development and implementation of State policy

Further, Article 267 (1) of the Constitution provides that: –

(1) This Constitution shall be interpreted in accordance with the Bill of Rights and in a manner that—

(a) Promotes its purposes, values and principles; (b) Permits the development of the law; and

(c) Contributes to good governance.

A perusal of the Constitution reveals that notwithstanding identifying the correct rules of application[17], the courts failed to consider other relevant provisions of the Constitution relating to the value and principle of good governance. The above provisions make it clear that when the Constitution is interpreted, good governance and integrity, which is a core national value and principle should be considered.

The fact that the Constitutional Court reached a conclusion that there isn’t a mandatory requirement to submit all loans to the National Assembly for approval does not seem to be in line with Article 63(2)(d) which is couched in mandatory terms. Clearly, the intention of the drafters of the Constitution was that the National Assembly should have oversight over all public debt as a matter of good governance, and separation of powers. Such a power does not vest in the Executive.

When interpreting Articles 63(2)(d) and 207 of the Constitution, the majority decision of the court did not adequately consider Article 114(1)(e) of the Constitution. The court stated that:

The above statement is true and correct because in terms of Article 114(1)(e), the role of Cabinet is to recommend loans and guarantees on loans to be contracted to the National Assembly. The provision does not state that all loans should be referred for approval. Our understanding is that this is to support Article 207(2) which states that legislation should prescribe with loans will require approval. This supports the view that the Constitutional Court was incorrect when they held that not all loans require approval from the National Assembly.

The Constitutional Court makes two conflicting statements when they state that the National Assembly is not responsible for approving all public debt, but on the other hand also state that Cabinet cannot approve public debt. If Cabinet cannot approve public debt as they only have the power to recommend to the National Assembly, the import of Articles 63(2)(d) and 114(1)(e) is that the National Assembly has the power to approve all loans, grants or guarantees as there aren’t any exceptions or provisions to Articles 63(2)(d). It was thus a misdirection on the part of the court to hold otherwise.

The court decided to limit its interpretation to whether all public debt needed approval. The court should have extended its interpretation to adequately discuss the failure by the Minister of Finance to submit the relevant public debt contracted since 5th January 2016 to the National Assembly. This would have required the court to discuss the adequacy of the Loans and Guarantees (Authorisation) Act and how it applies in the transition period before new legislation is enacted. This is important because under the principles of good governance, issues relating to public debt should have been dealt with comprehensively to give clarity to the executive on their duties, particularly in relation to public debt that does not need National Assembly approval.

Having held that the National Assembly does not oversight over all public debt, it would have been prudent for the Constitutional court to deal with this grey area given that there is certain public debt that the National Assembly does not need to approve, but Article 114(1) (e) does not permit Cabinet to approve the contraction of debt. This is an important aspect of constitutional interpretation given that any new legislation will have to comply with the Constitution and guidance given by the court.

Without prejudice to the above, as Zambia comes to terms with the years of unencumbered public borrowing, there is a need for introspection by the new administration in how it tackles borrowing in the future. There is hope that legislative proposals will be tabled that will give genuine effect to oversight functions of the National Assembly.

[1] Author is Kampamba Shula – Economist, Email Kampambahula@gmail.com for more.

[2] African Development Bank, July 2005, ZAMBIA: HIPC approval document – completion point under the enhanced framework.

[3] Government of Zambia, Statutory Instrument No 116 of 2013, The Loans and Guarantees (Maximum Amounts) , Loans and Guarantees (Authorisation) Act (Law, Volume 20, Cap 366)

[4] Statutory instrument no. 25 of 2014 – the loans and guarantees (maximum amounts) (amendment) order, of 2014

[5] Government of Zambia, Statutory Instrument No 22 of 2016, The Loans and Guarantees (Maximum Amounts) , Loans and Guarantees (Authorisation) Act (Law, Volume 20, Cap 366)

[6] Public Finance Management Act, 2018, National Assembly of Zambia.

[7] Kalala, Josiah (2021) “Dipak Patel v. The Attorney General [2020] CCZ 005,” SAIPAR Case Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 7.

[8] Dipak Patel v. The Attorney General [2020] CCZ 005, Dissenting Opinion at J20

[9] Dipak Patel v. The Attorney General [2020] CCZ 005, Judgment page J44-J45

[10] Kalala, Josiah (2021) “Dipak Patel v. The Attorney General [2020] CCZ 005,” SAIPAR Case Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 7.

[11] Dipak Patel v. The Attorney General [2020] CCZ 005, Dissenting Opinion at J25

[12] Steven Katuka vs. Attorney General, 2016, Constitutional Court of Zambia (Constitutional Jurisdiction)

[13] Public Protector for the Republic of Zambia v Indeni Petroleum Refinery Company Limited (1 of 2018) [2019]

[14] Chungu, C., 2021. Dipak P Dipak Patel v. The Minister of Finance and the Attorney General, SAIPAR Case Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 8. .

[15] Embassy Supermarket v. Union Bank Zambia Limited (in Liquidation) SCZ. No. 25 of 2007

[16] Chungu, C., 2021. Dipak P Dipak Patel v. The Minister of Finance and the Attorney General, SAIPAR Case Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 8. .

[17] Chungu, C., 2021. Dipak P Dipak Patel v. The Minister of Finance and the Attorney General, SAIPAR Case Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 8. .

[i] African Development Bank, July 2005, ZAMBIA: HIPC approval document – completion point under the enhanced framework

[ii] Government of Zambia, Statutory Instrument No 116 of 2013, The Loans and Guarantees (Maximum Amounts) , Loans and Guarantees (Authorization) Act (Law, Volume 20, Cap 366)

[iii] Statutory instrument no. 25 of 2014 – the loans and guarantees (maximum amounts) (amendment) order, of 2014

[iv] Government of Zambia, Statutory Instrument No 22 of 2016, The Loans and Guarantees (Maximum Amounts) , Loans and Guarantees (Authorisation) Act (Law, Volume 20, Cap 366)

[v] Public Finance Management Act, 2018, National Assembly of Zambia.

[vi] Kalala, Josiah (2021) “Dipak Patel v. The Attorney General [2020] CCZ 005,” SAIPAR Case Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 7.

[vii] Dipak Patel v. The Attorney General [2020] CCZ 005, Dissenting Opinion at J20

[viii] Steven Katuka vs. Attorney General, 2016, Constitutional Court of Zambia (Constitutional Jurisdiction)

[ix] Public Protector for the Republic of Zambia v Indeni Petroleum Refinery Company Limited (1 of 2018) [2019]

[x] Chungu, C., 2021. Dipak P Dipak Patel v. The Minister of Finance and the Attorney General, SAIPAR Case Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 8. .

[xi] Zambia National Commercial Bank PLC v Musonda and Others (4 of 2017) [2018] ZMCC 13 (13 June 2018); Constitutional Court of Zambia

[xii] Mutale v Attorney General & Another (18 of 2007) [2007] ZMSC 114 (24 July 2007); Supreme Court of Zambia

[xiii] Embassy Supermarket v. Union Bank Zambia Limited (in Liquidation) SCZ. No. 25 of 2007

[1] African Development Bank, July 2005, ZAMBIA: HIPC approval document – completion point under the enhanced framework

[1] Government of Zambia, Statutory Instrument No 116 of 2013, The Loans and Guarantees (Maximum Amounts) , Loans and Guarantees (Authorization) Act (Law, Volume 20, Cap 366)

[1] Statutory instrument no. 25 of 2014 – the loans and guarantees (maximum amounts) (amendment) order, of 2014

[1] Government of Zambia, Statutory Instrument No 22 of 2016, The Loans and Guarantees (Maximum Amounts) , Loans and Guarantees (Authorisation) Act (Law, Volume 20, Cap 366)

[1] Public Finance Management Act, 2018, National Assembly of Zambia.

[1] Kalala, Josiah (2021) “Dipak Patel v. The Attorney General [2020] CCZ 005,” SAIPAR Case Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 7.

[1] Dipak Patel v. The Attorney General [2020] CCZ 005, Dissenting Opinion at J20

[1] Steven Katuka vs. Attorney General, 2016, Constitutional Court of Zambia (Constitutional Jurisdiction)

[1] Public Protector for the Republic of Zambia v Indeni Petroleum Refinery Company Limited (1 of 2018) [2019]

[1] Chungu, C., 2021. Dipak P Dipak Patel v. The Minister of Finance and the Attorney General, SAIPAR Case Review: Vol. 4: Iss. 2, Article 8. .

[1] Zambia National Commercial Bank PLC v Musonda and Others (4 of 2017) [2018] ZMCC 13 (13 June 2018); Constitutional Court of Zambia

[1] Mutale v Attorney General & Another (18 of 2007) [2007] ZMSC 114 (24 July 2007); Supreme Court of Zambia

[1] Embassy Supermarket v. Union Bank Zambia Limited (in Liquidation) SCZ. No. 25 of 2007